Your first job, awesome readers: go to the comments and tell me yes or no if you have heard of the story of Baucis and Philemon.

And, if you are so inclined, tell me where you first found about it.

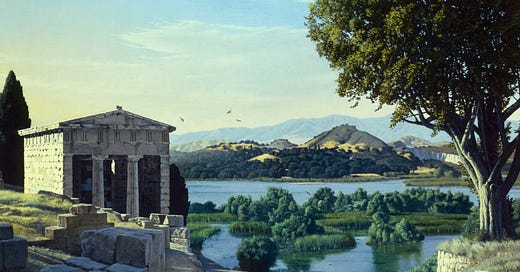

Next, take a look at the painting below, by David Ligare, an artist who specializes in enormous canvases of “hyperrealist” art.

I have always loved this work, mainly because the landscape reminds me of my native California with its tawny hills dotted with live oaks.

It is one of the latest transformations of the story of Baucis and Philemon, a creative process that began at least 2,000 years ago.

If you haven’t ever heard of Baucis and Philemon, never fear. A synopsis is dead ahead.

But understand that it’s not really Greek mythology. An explanation of that is also dead ahead.

The story goes that Zeus and Hermes (or Jupiter and Mercury, depending on your cultural context) decided to descend to the earth disguised as mortals to check on how people were doing on the virtue of hospitality. One of Zeus’s important concerns was to make sure people were treating traveling strangers with generosity and grace.

The two gods happen upon a community of mean, ungenerous folk who refuse them a meal and a bed for the night. All but one household fails the hospitality test: that of Baucis and Philemon.

Baucis and Philemon, wife and husband, respectively, are an elderly couple who live simply by themselves in a small house near the margin of their town. When the disguised Zeus and Hermes arrive, the hospitable B&P busy themselves making an impromptu feast for the visitors.

In the ancient Roman version of the story (more on this version below), the couple are astonished when their wine bowl becomes bottomless. However much wine they dip from it, it never lowers its level.

B&P then realize they must be in the presence of immortals, and in reverence determine an animal sacrifice is in order. And what will that be? Their pet goose, a true sacrifice.

Zeus and Hermes reassure the couple that they need no sacrifice. Instead, they flood the town and drown its wicked inhabitants, preserving only B&P, and transforming their little house into a marble temple.

The gods then ask B&P to make a wish, as a reward for their good deeds.

Their wish: to look after the temple that was their house, and to die at the same moment, so neither one of them has to mourn the other.

Granted! And at the end of their lives, B&P are transformed into trees with trunks that intermingle. So the pious mortals are united forever.

The Roman version I’ve just quoted is from the poet Ovid (43 BC - 17 AD), who wrote a monumental poem about Greek mythical transformations called the Metamorphoses.

Astonishingly, Ovid’s version is the only one we have about Baucis and Philemon anywhere in ancient literature.

We don’t even know if any actual Greeks ever told this story.

Its life as a famous story starts with Ovid, and goes through many transformations up until David Ligare’s painting (scroll up—you can see the temple and the flooded village, now a lake).

One of the most well-known transformations is in Nathaniel Hawthorne’s A Wonder-Book for Girls and Boys (1852). This book, which became super-popular and almost singlehandedly launched the Greek-myths-for-kids phenomenon, is probably responsible for any of you schoolchildren or former schoolchildren actually knowing the story.

So where did it come from? What was Ovid’s inspiration?

No one really knows. But there are fun clues.

Though there is no specific mention of Baucis and Philemon in Greek mythology, there is a story from Greek mythology that somewhat resembles it. This is in the poem called the Hecale, by the Hellenistic poet Callimachus (310-240 BCE).

In an episode from this poem, the hero Theseus meets Hecale, an impoverished old woman, on his way to capturing the Bull of Marathon. She gives him humble hospitality, for which he is grateful. On his way back from his task, he discovers the woman has died. In gratitude, he creates a “deme” (neighborhood) of Athens named after her, and establishes there a shrine to Zeus, the god of hospitality.

This story is not really mythology strictly speaking. It is a side-story, and may have been invented to explain why there was a deme in the region of Athens called Hecale. But the traces of Baucis and Philemon are there—an old woman, poor, humble, gives hospitality to someone greater than she, and her home becomes a religious space in response to her good deed.

But that isn’t quite the story, is it?

For one, this story happens in Athens, the heart of Greece, and Baucis and Philemon live in Phrygia (Asia Minor, modern Turkey). And as we have seen time and time again, this land, which is sort of intermediary between the creative West Asian areas of Mesopotamia, Syria, and Lebanon, is often a place from which Greek poets take their inspiration.

Baucis and Philemon and the Bible

So here we go—let’s look east of Greece.

Several details of Ovid’s story resemble those in certain stories of the Hebrew Bible (Old Testament), and by contrast, there is a story in the New Testament that recalls Baucis and Philemon in reverse.

First, the idea that God, gods, or angels visit humans, taking on human form: that idea is present in the book of Genesis (18:1-15), where “three men” visit the wandering Aramite Abram and his wife Sarai, who give them eager hospitality.

They in turn give Abram and Sarai a boon, telling them that Sarai will give birth to a child who will found a race (the Israelites) more numerous than the stars.

Abram and Sarai (who are renamed by the men Abraham and Sarah) are both old, like Philemon and Baucis, and, again like Ovid's pair, childless.

The “three men” have been allegorized by some Christian thinkers as the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, but it’s clear in any case that these visitors are not mere men, but at least messengers of the God who is showing favor to the couple.

Okay. Now think of another couple, also in the book of Genesis (Chapter 6-9), who are favored by God because of their faithfulness to God: Noah and his wife.

Here, there is no visit from God, but Noah receives the message that he is to build an ark to be saved from floodwaters. God has determined that the world is irredeemably in error, and so God must start again from scratch, preserving only Noah, his wife, his family, and the animals of God’s creation.

Similarly, only Baucis and Philemon are preserved from the flooding of the village whose inhabitants made the fatal mistake in Ovid’s tale of denying hospitality to Jupiter and Mercury.1

Now the reverse part: In the New Testament, in the Book of Acts (14:8-20), the Christian apostles Paul and Barnabas visit Lystra, a town in Asia Minor (modern Turkey), not far from the region of Phrygia where Ovid has set the story of the faithful couple.

In Lystra, Paul is able to heal a man who has been disabled since birth, unable to walk. When the townspeople find out about the healing, they get it into their heads that Paul is Zeus and Barnabas Hermes in human form.

Then there is the famous verse from the New Testament, in the Letter to the Hebrews (13:2):“Do not neglect to show hospitality to strangers, for thereby some have entertained angels unawares."

Tree cults in West Asia

Finally, an intriguing (in-tree-ging?) idea that may slot into our investigation of West Asian influences on this story—specifically, now, religious.

Ancient West Asian religion often featured a tree goddess. The Canaanite (Lebanese) goddess Asherah was a tree goddess. A goddess similar to her, Astarte, was associated among other things with the palm tree. In Mesopotamia, the goddess Ishtar had to do with the Tree of Life.

In fact, Helen, the famous character from the Trojan War, was worshipped in Sparta as a tree goddess, which has caused scholars to speculate on her origins as originally an Asherah or Astarte-type goddess.

Humans or human-like beings, identified with tress.

And one more parallel: Abraham was camping near an oak tree (called the “Oak of Abraham,” part of the “Trees at Mamre”) when the three messengers of God visited him.

So there is a coupling of trees with this story that is at home in an ancient West Asian context.

In conclusion…

Ovid may not have had any idea of any of this. We really don’t have any idea about what inspired him to include the story in the Metamorphoses.

There’s a lot more to the story than its sources, of course!

But I wouldn’t be surprised if Baucis and Philemon come from a folktale that is native to Asia Minor, and influenced by the tales that come from farther east.

Finally…

If you think about it, the familiarity of the story with those of the Hebrew Bible was probably the decisive factor that made Nathaniel Hawthorne include it in his Wonder-Book for Girls and Boys. Hawthorne was a strong Christian, and though he admired Greek mythology, he was equally concerned with telling stories that would be edifying to his young audience.

The Greeks had their own flood story, featuring Deucalion and Pyrrha.

I do not recall having heard this story before.

I am familiar with the story (perhaps because we read excepts from Ovid in High School Latin?) but I did not recognize/remember the names.