You might think that I, as a mythologist, would be a big fan of Joseph Campbell, the most famous popular mythologist of the late-twentieth century.

Yeah, not so much.

Speaking of subscriptions: It is a thing most to be desired to find worthy Substacks. I already subscribe to more than I can read. But this one on women’s stories is a good one, not your run-of-the-mill blah blah blog.

Bonus: like me, she’s not big on Campbell’s way of looking at mythology.

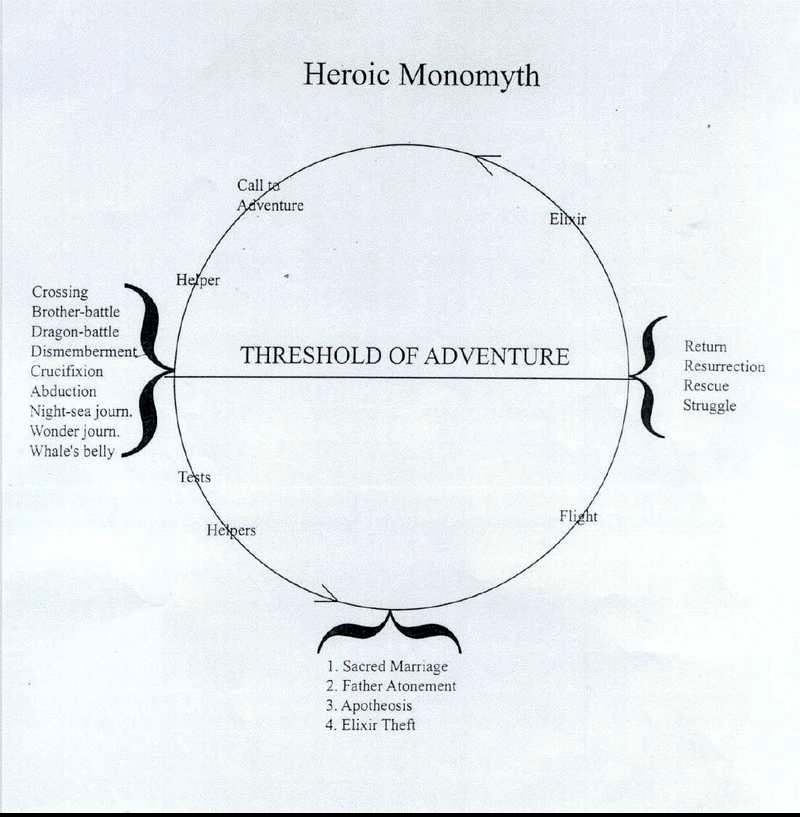

Joseph Campbell is best known for the idea that the original Star Wars movie is based on his theory of the Hero’s Journey. Campbell sums up the theory in one paragraph (see below1), which crystalizes the idea that all myth is pretty much the same story told over and over.

Yes, just one (mono-) story.

And worse, Campbell uses the theory to justify the idea that you should live your life as if it’s a personal adventure.

He’s the one that made famous the phrase “Follow Your Bliss.”

Not something usually that women have had the ability to do.

This (“The Lady Hero’s Journey”) is almost certainly

the funniest thing I’ve ever read on McSweeney’s.

Someone has to do all the work to make society run so heroes can go off into the threshold of adventure to follow their bliss, and usually that’s been women.

I have nothing against the idea that life can be an adventure, but in these latter days of telling children they can be anything they want to be, I think we’ve swung the pendulum a bit far.

We also need people who are interested in helping, being part of a cohesive community. Sacrificing their own needs for those of others.

So that it’s not 20 percent of the people doing 80 percent of the work.

What has this rant to do with Greek mythology? Well, that’s the point.

Joseph Campbell didn’t do a lot of mentioning of Greek mythology in his work, because Greek mythology doesn’t have much to do with the Hero’s Journey.

Despite what people might have told you, Ancient Greek tales aren’t about the hero fulfilling his own personal mission of fulfillment.

Greek heroes, strangely enough, are about family.

This is an idea that is too long to do justice to in one Substack post, but it’s important because it helps us to understand the unique creative impulse of the ancient Greeks.

What they were about—what they valued.

I emphasize that influences are extremely important in storytelling and creativity in general, but the particularity of a culture’s stories is just as important.

(BTW—I talk about this in a different post about non-Greek stories.)

So let’s talk (briefly) about Achilles.

Achilles is usually the hero we think is following his bliss. He’s the one who, in the Iliad, withdraws from the Trojan War because he’s been insulted by his commanding officer one too many times, and he’s gonna show that so-and-so just how important he is to the Greek war cause.

Achilles has an enviable pedigree. He’s a demigod, the son of a famous warrior and a literal sea-goddess. Rumor (or myth) has it that, as a baby, he was dipped into the Styx, the River of Death, and came out invulnerable, except for his ankle.

His bliss? To live a short but memorable life.

For all that, he’s not perfect on his own. He has to ask his goddess mother, Thetis, to go to Zeus, who will make the Trojans fight better—much better—while Achilles is on strike, so that the Greeks get the idea crystal clear who is the Best of the Achaeans.2

Keep that in mind—Thetis going to bat for her son with Zeus.

At first, Achilles’ plan works like a charm. With the Greeks’ star player out of the lineup, the Trojans gain confidence. With Zeus strengthening them, their confidence soars.

After things get bad enough, Agamemnon, Achilles’ commanding officer, seeks reconciliation with the demigod he insulted. He had taken away Achilles’ war-prize, the beautiful princess Briseis. Now he offers to restore her to Achilles’ tent.

Achilles has already admitted that he really loves Briseis—that’s one of the reasons he was steamed about the insult. Briseis is as close to a wife as Achilles has had in his life. Keep her in mind, too.

But Achilles demurs. Agamemnon refuses to apologize in person. Agamemnon wants to save face, even as he is being substantially shamed for his misstep.

This half-apology of Agamemnon is not enough for Achilles. And so he continues his strike.

Things get worse. The Trojans are throwing blazing torches onto the ships of the Greeks, the only way the Greeks can flee if they have to.

So Patroclus, Achilles’ very best friend (and, in some versions of the tale, his lover), comes and begs Achilles to have mercy on the Greeks.

“Even if you don’t come back and fight,” he says, “lend me your armor. As soon as the Trojans see it, they’ll think you’re back, and they’ll retreat.”

Against his better judgment, Achilles agrees.

“But don’t try to take the city, Patroclus. Fate has not given you that privilege. Fall back once the Greek ships are safe again.”

Patroclus agrees. He’d agree to anything at this point.

But he doesn’t ultimately take Achilles’ advice.

Buoyed by the confidence of wearing the armor of the Best of the Achaeans, and taking advantage of the terror that that armor instills in the Trojans, he creates a wide swath of blood and death on his way to the walls of Troy.

There, he climbs a ladder, seeking to enter the city.

That’s where Apollo, the god of boundaries, draws the line.

He knocks Patroclus off the ladder, stunning him.

Hector, the greatest Trojan hero, then takes both Patroclus’s life and Achilles’ armor.

Four precious people: a family

So far in this story, Achilles has done just about nothing. He has caused everything, but only sat in his tent.

Now that his best friend has died, Achilles springs into action.

First, he asks his mom for one more favor: new armor, made by the creative Hephaestus.

Then he wades back into the war. He’s looking for revenge.

On his way to find Hector, the slayer of Patroclus, he kills about everything in sight.

He even fights a river.

Once he finds, duels, and kills Hector, he’s not satisfied. He despoils the body of his enemy and refuses to give it back to the Trojans.

He is that mad and grief-crazy.

It takes a secret night-time visit from Priam, Hector’s father, the king of Troy, to soften Achilles enough to do what is honorable.

It is an absolutely heart-breaking scene, and a one-hundred percent Ancient Greek scene, Priam and Achilles together.

Because, finally, Achilles recognizes that family is the most important thing in the world.

What is it that makes Achilles relent from his anger and give back the body of Hector?

Most of all, it’s this last speech of Priam:

Honor the gods, Achilles, and take pity on me.

Remember your father. But I suffer more—

I have done what no father has ever faced:

I have reached out my hand to my children’s killer.”

Iliad, Book 24.502-506 (my translation)

It’s an incredibly intimate moment, with Priam, the great king and proud enemy of the Greeks, on his knees, in abjectness, appealing in the most shameful way for what by right should already be his.

He’s only asking for his family to be made whole.

Achilles does think of his father. He and Priam both weep. Both of them have reason to grieve.

Then Achilles does another extraordinary thing: he invites Priam to dinner.

This communion, a unity of grief, underscores how important human connection is, and how unimportant it is to have fame and glory and possessions, the conventional things that heroes are supposed to value.

Yes, Priam has brought a lot of loot to give in return for Hector’s body. That’s only natural in this situation.

But it’s not the deciding factor here.

Achilles finally realizes that, by valuing himself over others, he has lost the only family he has ever had.

He has undervalued his mother, who twice did what he asked, but whom he never thanked or honored.

He has undervalued his father, by leaving him at home undefended.

He has undervalued Briseis, by not taking her back when he could.

And he undervalued Patroclus, by allowing him into the battle when he himself should have taken responsibility for the safety of the army that was relying on him.

That’s the soul of the ancient Greeks: showing, through the story of a hero, that family togetherness is really the only thing that matters in this world.

A last myth, in Achilles’ words

When Achilles invites Priam to dinner, he gives him this myth as an example to follow:

…Let us take thought of a meal.

Once, beautiful Niobe did the same,

though the gods killed her children,

six daughters, six sons. Terrible.

Apollo slew the sons with his silver bow,

and Artemis shot the daughters,

since Niobe had challenged Leto,

saying that the goddess had borne only two,

while she was mother to many;

and so the two killed the many.

For nine days they lay in their blood

and no one buried them—

Zeus had turned the townsfolk to stones.

but on Day Ten the gods did the burying,

and Niobe, exhausted from grief,

thought again of nourishment.Iliad, Book 24.601-613 (my translation)

I’ll just leave that there.

So, no, Achilles’ story is not about crossing over into the threshold of adventure and battling dragons. He doesn’t even really succeed in coming back from adventure and having a family, despite his newfound wisdom. He has chosen a short life, and he gets it. He finally is killed by an arrow to his vulnerable ankle.

Greek mythology is filled with stories like this: heroes who would be better off, happier, if they could go home and be with family again. But they are fated to be examples—negative role models—to the ordinary people of Greece.

The myths were speaking to those who told them: Do not seek to be anything you want to be, follow your bliss, or hear the call to adventure.

Instead, live your life for those closest to you.

It’s not an American ideal.

But then, it’s not supposed to be.

All cultures have their own values. We should respect that.

We should celebrate it.

Campbell’s summary of the monomyth:

The mythological hero, setting forth from his common-day hut or castle, is lured, carried away, or else voluntarily proceeds, to the threshold of adventure. There he encounters a shadow presence that guards the passage. The hero may defeat or conciliate this power and go alive into the kingdom of the dark (brother-battle, dragon-battle; offering, charm), or be slain by the opponent and descend in death (dismemberment, crucifixion). Beyond the threshold, then, the hero journeys through a world of unfamiliar yet strangely intimate forces, some of which severely threaten him (tests), some of which give magical aid (helpers). When he arrives at the nadir of the mythological round, he undergoes a supreme ordeal and gains his reward. The triumph may be represented as the hero’s sexual union with the goddess-mother of the world (sacred marriage), his recognition by the father-creator (father atonement), his own divinization (apotheosis), or again — if the powers have remained unfriendly to him — his theft of the boon he came to gain (bride-theft, fire-theft); intrinsically it is an expansion of consciousness and therewith of being (illumination, transfiguration, freedom). The final work is that of the return. If the powers have blessed the hero, he now sets forth under their protection (emissary); if not, he flees and is pursued (transformation flight, obstacle flight). At the return threshold the transcendental powers must remain behind; the hero re-emerges from the kingdom of dread (return, resurrection). The boon that he brings restores the world (elixir).

“Achaean” is a synonym for “Greeks.” Homer uses the phrase (aristos ton Achaion) quite a bit in the Iliad.

I *do* appreciate Campbell's work although I am skeptical about the "universal" nature of his model -- similar to how I feel about Carl Jung.

Be that as it may, at a corporate retreat earlier this year, one of the presenters cited "Hero" in a PowerPoint slide, which was going WAY too far!😆