Recently I was reminded of a truth that I hold dear: myths are not simple random stories that primitive cultures tell because they don’t have science.

“Explanations.” That’s what you still get much of the time when you read about the significance of myths. This is especially true in K-12 education.

This used to be standard for non-Greek mythology (and even some Greek myths, too). The Greeks were lionized as having complex stories that were more literature than myth.

Other cultures? Simple, primitive, inferior.

But I’m here to tell you, if you don’t already know, that the stories people tell are always carefully chosen, important to their people, and deeply felt.

If a non-scientific story includes some kind of interpretation of a natural phenomenon, the main purpose is not to “explain” that phenomenon. An explanation takes a few minutes and you’re done.

For an actual story that you’re going to tell over and over again, there has to be something more complex going on—something that the culture is attempting to reinforce.

This is usually some type of religious, social, political, or psychological value that is near and dear to the hearts of those people who live where the story is being told.

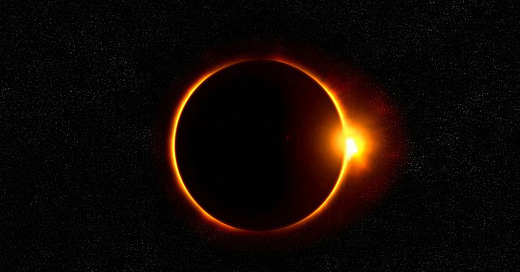

Last year’s solar eclipse is a good example of this. At that time I heard about a bunch of stories that various cultures around the world tell about eclipses. Every one was unique.

One of them, a Maori (indigenous New Zealand) myth, talked about an eclipse being the dance between the sun god and the moon goddess.

What a lovely thought. Those Maori people were so sweet and simple, weren’t they?

I looked online to investigate more about that story, but surprisingly, Google (and JSTOR for that matter) knows nothing about it (Here is a place you can look if you want to survey eclipse stories on a surface level).

My rabbit-hole dive did yield one article that decided to expand on the eclipse stories by including this one, apparently about why the day is as long as it is:

The Maori people of New Zealand tell a tale about a long-ago time when the days were shorter than they are now. The hero Maui often heard his brothers lamenting the lack of light during the day. He decided to solve the problem by taming the sun. Although his brothers were skeptical, they and their tribe helped Maui weave a net out of flax.

Maui and his brothers then set out to the east to find the sun's resting place. They covered the entry to the sun's cave with nets and smeared themselves with clay to protect against the sun's heat. When the sun emerged, it fought and struggled in the nets, but the brothers held firm. Maui began to beat the sun — some stories say he had an ax, others a club made of the jawbone of an ancestor — until the star was so weakened that it could no longer race across the sky. According to the legend, that is why the sun travels so slowly in the sky today.

This is fun, an apparently simple story that no one from a scientific culture would believe. Ha ha, snaring the sun with a flax net. Completely childish, no?

Maui in this story is that same Maui from the Disney movie Moana, the Heracles-like Polynesian culture hero who is responsible for giving humanity much of its ability to control the world.

In the popular song “You’re Welcome,” Maui outlines what he has done in a boasting fashion, giving the impression that he is pretty much Heracles, who does what he does mostly on his own (not even with the help of his brothers).

And that old chestnut about explanations? Here it is, from the song:

Kid, I could go on and on

I could explain every natural phenomenon

I love that lyric. It’s a good song.

But apparently Disney got it wrong, as Disney does.

Here is an excerpt from a Smithsonian magazine article well worth reading:

Tongan cultural anthropologist Tēvita O. Kaʻili writes in detail about how Hina, the companion goddess to Maui, is completely omitted from [Disney’s version of the] story.

“In Polynesian lores, the association of a powerful goddess with a mighty god creates symmetry which gives rise to harmony, and above all, beauty in the stories,” he says. It was Hina who enabled Maui to do many of the feats he uncharacteristically brags about in the film’s song “You’re Welcome!”

Here, possibly, is an echo of that idea that the sun god and the moon goddess are dancing with each other during a solar eclipse.

But Professor Ka’ili is pointing out in this quotation that the story is not a simple one. His article goes on to outline an intricate, fascinating set of cultural truths about Polynesian society, including a note about that sun-snaring story I quoted above:

Depending on the version, the goddess Hina (or Hina-like goddess) is Māuiʼs grandmother, mother, wife, or sister. In one Māori version, Hina is the oldest sister of Māui. She taught Māui how to use her hair to plait a supernatural rope for snaring the sun and lengthening the days.

By using her hair, Hina infused Māuiʼs sun-snaring lasso with mana. In one legend, Māui attempted seven times to capture the sun and failed. He finally succeeded on the eighth try when he used a rope made from Hinaʼs hair.

This is cool. This makes more sense. This is indeed about symmetry, harmony, and beauty. It’s about complementarity. It’s not about some super-strong guy who does what he does all on his own.

Nor is it only or even primarily about why daylight lasts 12 hours. It’s not really an explanation at all. It’s an opportunity to use natural phenomena to reinforce the values of a culture.

What’s the lesson? What is the takeaway? Don’t mess with Maui when he’s on a breakaway?

(Love the Moana soundtrack.)

But know this: Human beings are complex creatures, and we’ve been thinking about stuff for thousands and thousands of years.

Like language, which can be incredibly intricate, mythology is a detailed and powerful thing.

It’s just that not every culture has been given the privilege of place that Greek mythology has.

"Maui began to beat the sun — some stories say he had an ax, others a club made of the jawbone of an ancestor."

This guy is beating on the Sun with his grandpappy's jawbone!? That's the most metal thing I've ever heard.