Way back when, there was a film about baseball called The Natural, in which a mysterious woman, Harriet Bird (Barbara Hershey), asks the main character, Roy Hobbs (Robert Redford), a mysterious question:

“Have you ever read Homer?”

“The only homer I know has four bases,” Hobbs replies.

And that’s what this post is about: have you ever read Homer, the one who is rumored to be the author of the Iliad and the Odyssey?

Or is the only homer the one with four bases?1

It’s a very old question, one that may never have a definitive answer.

But there’s a new book out that tries, once again, to make an educated guess.

This is Robin Lane Fox’s Homer and his Iliad. As the title suggests, he is definitely in the Homer-exists camp.

Disclaimer: I haven’t read Homer and his Iliad yet, only reviews (shout out to fellow Substacker Joel J. Miller, who recently sponsored an extensive review essay by Jordan Poss), but I definitely have opinions.

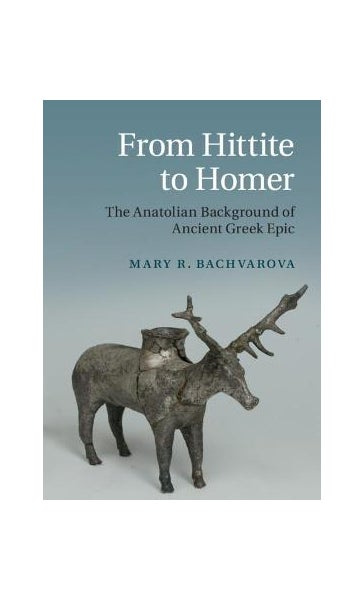

However, there’s another book out, not as recently, that argues that the Iliad (and with it, the base of Greek mythology) is a work nurtured in a community of poets. This book is From Hittite to Homer, by Professor Mary Bachvarova.

This is the question of two books and two scholars: is the Iliad the work of a one-in-a-million genius, or was it, essentially, written by committee?

I need to confess, first, that I have long been a Homeric unitarian, which is to say, I would lean toward Lane Fox’s thesis of the one-in-a-million genius.

However, after reading From Hittite to Homer, and another book on the nature of creativity (The Runaway Species, by Anthony Brandt and David Eagleman), I have changed my opinion to the other side.

There most definitely wasn’t one Homer.

So what’s this about Steve Jobs in the subtitle of my post? There was definitely one of him. What’s going on with that, you ask?

In The Runaway Species, the authors emphasize that creativity doesn’t happen in a vacuum: geniuses of all stripes always rely on those that come before them (and often, people working alongside them) to come up with their new creations.

Here are Jobs’s thoughts on the matter, quoted in Brandt and Eagleman’s book:

Creativity is not just connecting things. When you ask creative people how they did something, they feel a little guilty because they didn’t really do it. They just saw something. It seemed obvious to them after a while; that’s because they were able to connect experiences they’ve had and synthesize new things.

Steve Jobs was lionized as being the genius inventor of the iPhone, but The Runaway Species explains that this invention was really just the culmination of a lot of work by a lot of people on prototypes and versions of it.

So do we conclude that our Iliad—like the iPhone, certainly a genius invention—is the major or sole work of a person named Homer, or do we emphasize the prototypes and creative community around it?

For me, it’s the community.

I don’t know if Homer ever existed—we have no reliable record that he did, although he is popularly known as a blind poet from a coastal town on the Aegean Sea that is now in the nation of Turkey.

Neither the Iliad nor the Odyssey include any biographical details about the author, just a humble first-person invocation of a goddess of inspiration.

Sing, goddess, the rage of Achilles, son of Peleus…

This line indicates that the poet considers him- or herself a conduit for a story that is not the poet’s own. It’s the Muse that sings, and the poet is the medium of transmission.

The line also suggests that whoever ended up creating it is aware of the long history of the story of the Trojan War and the specific episode from it that is the dominant storyline of the Iliad.

Now, no one that I know of disputes that there was an oral tradition of epic poetry that dates back hundreds of years before Homer. Just how many hundreds is still very much a part of the debate.

But did one guy, like Steve Jobs, put together all the prototypes into one magnificent whole, or was there never just one essential author?

This is where From Hittite to Homer comes in.

Professor Bachvarova very carefully and granularly pulls apart the different strands of the Iliad—and there are several different strands—and considers their sources.

This practice helps us to understand that the Iliad is not like a traditional novel or poem from modern times—something like The Great Gatsby—where it’s clear the author is telling an original, focused, unitary, and thematically coherent story.

Instead, the Iliad has a dominant storyline, about the rage of Achilles, who has been offended by his commanding officer, Agamemnon, and so withdraws from the war, and causes large amounts of harm thereby. But several other subplots and side stories have made it into the poem as well.

I’ll confess, too, that I don’t like to read the Iliad straight through, all 24 chapters, as I would a modern novel. That’s because if you want to stick with the rage of Achilles, you have to skip whole chapters. There’s a lot of material in the Iliad that doesn’t, as we say, advance the plot.

Stuff that a modern editor might consider striking out.

That doesn’t mean the Iliad isn’t an amazing work, or that it couldn’t have been stitched together by one genius.

But it does mean that the emphasis of this tale—this set of tales, really—should be on the different communities that originally sang the tales, rather than on one genius who put it all together.

Again, unlike a novel such as The Great Gatsby, From Hittite to Homer points out that the rage of Achilles is not an original storyline that was dreamed up whole. The Epic of Gilgamesh, a poem from Mesopotamia that predates the Iliad by centuries, clearly has influenced the story of Achilles.

Professor Bachvarova also lists other stories from West Asia that have been woven into the fabric of the Iliad, with exotic titles such as The Cuthean Legend of Naram-Sin. The Hittites, who lived very near the Greeks (and the city of Troy) in Anatolia (modern Turkey), are likely intermediaries between the Greeks and these more ancient and more distant stories.

Further reason to see this creation as a work of collaboration and influence, rather than a pristine, gem-like masterpiece.

Bachvarova persuasively argues as well that we have a large amount of evidence for the existence of communities of poets who worked on the fundamental base of Greek myths.

She postulates that the final text of the Iliad was probably written down and fixed (for the most part) by about 700 BCE, some three centuries after the first Greek versions of a story about Troy began to be sung.

That’s a lot of time for revision!

Still and all, maybe (just maybe) we could have the best of both worlds by saying that bunches of people contributed to the final product of the Iliad, but only one person actually decided on the final text.

Sort of like Steve Jobs and the iPhone.

To me, that’s very romantic, and I am a romantic, and an author myself with a lot of novels under my belt that are definitely my creation and not a result of collaboration with others.2

But I don’t believe in the romance of the creative genius with this particular poem.

That’s because here, I believe more in the romance of community—and the reality of what life was like in the ancient world.

Here, at the very beginning of European literature, when the alphabet was just becoming a tool, and no one was sitting down alone at a desk and scribbling out immortal lines of poetry, I think it’s more appropriate and real to believe that those who worked on this poem were almost constantly in contact with others, singing lines that they then worked out with each other, building story on story, integrating, refining.3

Poets also tried to outdo each other as they entertained their audiences. As Professor Bachvarova puts it:

In the crucible of competition among poets in festival contexts, the various versions of the Iliad… were fused together to create the Iliad that has proved to be one of the foundational texts of Western culture.

I believe there were probably a hundred or more genius Homers, all of them distilling their work into what ended up being the artifact of a genius area and time of the world—from Greece to Anatolia to Cyprus to Syria to Mesopotamia from 1000 to 700 BCE.

They created a work that would inspire others who did scribble by themselves (when that became a thing) and develop a more focused and unitary creation.

So the pendulum has swung for me. Not one Homer, not one genius writing a masterpiece, but a community of Homers doing what had never really been done before in the Greek world.

I will let you know if the pendulum swings back.

The other well-known Homer, Simpson, is not part of this particular post. Maybe another time. :)

I did write one novel at the age of 15 that was a collaboration with my best friend. He would write a page on his Royal manual typewriter, and then I would write a page, and so on. That ended up being over 250 pages long.

I am reminded of that episode in the movie School of Rock where Jack Black, as leader of a student rock band, finds out that one of his students has been writing a song on his own. “You got lyrics? Hook me up,” he says. “No more secret songs.” They then play the song together and revise it to make it even better.

Just came across a couple of your article and find your posts very interesting. I could help but draw a conclusion with questions on who was Homer(s). You had also wrote about two gates (pylai). The first of these, made of horn, was the source of the prophetic god-sent dreams. Could it be a possibility that one writter used this ability? I can see validity for a single person in this regard. I believe Nicola Tesla made a reference about his thoughts coming from a higher source, where he considered himself like a radio receiver. I lean this direction, because the stories are far too complex and intertwined for it to be one man's thoughts. Not to mention it's astrological parallels. Just as Heraclitus had wrote that he (Homer) was a wise astrologer.

Thanks for this thoughtful comment, Warren. I think it is true that inspiration often comes from an unexplained source. That's why the Greeks believed in the Muses, goddesses who "sang" through them. It's a clever way of expressing that what you have created is somehow not your own.

Dreams are incredibly creative. I once dreamed the background for an entire dystopian novella one night, and wrote 5,000 words the next day to get it down before I forgot it. I am not a speculative fiction writer and I am not all that interested in dystopian stories, but I know a Muse's prompting when I see it. The idea of the gate of horn that brings dreams that are accomplished seems to me another expression of the recognition of the subconscious among the ancient Greeks and Romans.

Thanks also for the Tesla reference. I love hearing about the inspiration for technological innovation.