I feel a little like the Most Interesting Man in the World from that beer commercial:

I don’t read a lot of books all the way through, but when I do, they’re good.

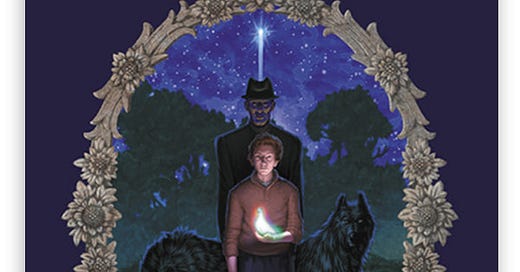

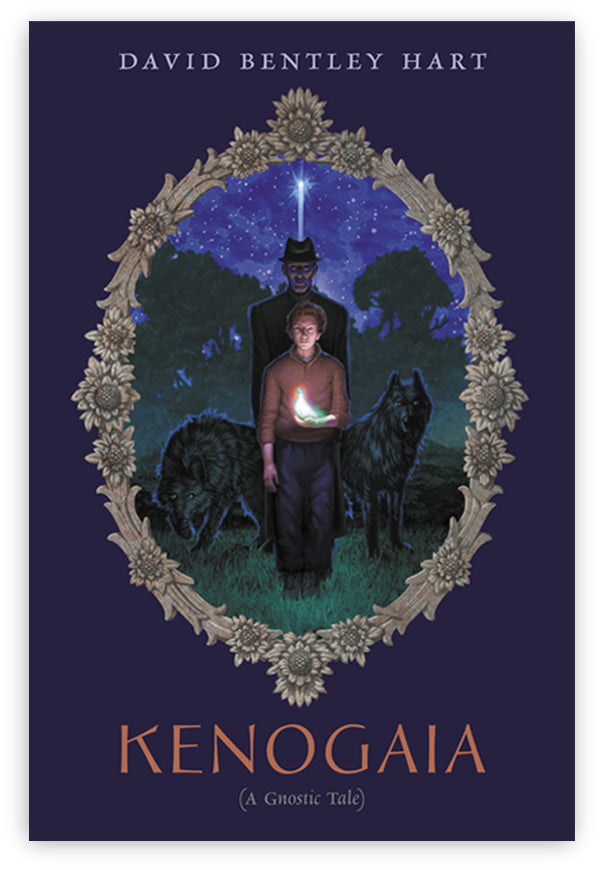

That’s why I had a fine time with philosopher and theologian David Bentley Hart’s Kenogaia, a fantasy novel that’s billed as “A Gnostic Tale.”

It’s an odd little book that resists easy categorization. The principal heroes of the book, a girl and a boy, are 13 years old, so you’d think, okay, middle grade or young YA.

But the characters who drive the action, though they appear as young as the main characters, are actually thousands of years old. More on that below.

Then there’s the language (or rather, languages) used, which is bejeweled with Hart’s characteristically erudite vocabulary and turns of phrase (e.g. “alacrity,” “aethers,” “ominously plausible,” “perfidy,” “scintillations,” “medallioned frieze,” to name a very few).

His descriptions are a riot of visual detail:

The director’s office was impressively opulent: superb wooden paneling on every side and wooden coffering overhead, a handwoven carpet patterned with intricate images of vines and fruits and flowers, green, red, yellow, and violet against a rich midnight blue, chairs of lacquered rufous wood and polished ruby leather, an immense desk of scrolled and fluted ebony drenched in the morning brilliance pouring down from two more skylights, and beyond the desk three enormous windows with large panes framed in airily delicate brass.

The reader might also benefit from knowing Latin and ancient Greek, because many of the characters and lots of vocabulary come from these languages (Dr. Axiomorpha—Greek for “Worthy in Shape”—is a villain marked by her shapeliness; telephones are called “anemophones” —in Greek, “wind sounders”).

(Substack is red-underlining all the weird stuff as I type).

Even by the standards of Madeleine L’Engle, the famous Young Adult author (A Wind in the Door, A Swiftly Tilting Planet, A Wrinkle in Time), who counseled authors never to write down to a child’s vocabulary level, this is dense stuff.

Still, the story shares many characteristics with a traditional fantasy novel for young people. In terms of content, it’s PG, with (happily) no cursing at all.

In fact, it feels very reminiscent of C.S. Lewis’s Chronicles of Narnia. I heard echoes of all of the seven books of that series, not to mention a corrective nod at Lewis’s book about Heaven and Hell, The Great Divorce.

There were steampunk elements (“aerial barges” powered not by liquid fuel but by “vapors”), a whiff of The Matrix movie and C.S. Lewis’s Perelandra science-fiction trilogy, pistols and cannons, magic, ghosts, a dragon (not fire-breathing), werewolves, a talking bird, marble-white trees with blue leaves…

<deep breath>

But all of this richness is structured in a world inspired by Gnostic mythology, a belief system of the first few centuries after Christ, which existed side by side with early Christian belief. Gnostics had a variety of different ideas about the nature of the world, but one of the dominant ones was that our world is a prison for our souls created by a false god, and that the goal of life is for souls to rise back to our original place in the heavens.

This is the impulse for introducing the most important characters for the story, the brother and sister duo Oriens and Aurora, the child-appearing but millennia-old characters who drive the action.

Oriens is a bit like Aslan, the lion who acts as the Christ figure in the Chronicles of Narnia. Oriens has descended from the true world of the heavens in the incarnation of a human boy to find Aurora, who has been kidnapped by the false god of the false world. In order to help him in this unfamiliar world, he enlists the help of the 13-year old youths, Michael Ambrosius and Laura Magian.

This is where, for me, the storytelling really departs from the YA realm and carves out its own idiosyncratic genre.

Oriens is wise, calm, and in possession of magic jewels that pretty much can do anything you want them to do. Whenever the trio gets into a scrape, the jewels are there to bail them out.

Similarly, once Aurora is found, she turns out to be pretty much invincible as well.

Then there is the talking bird, who provides critical intelligence at the proper moment.

So Michel and Laura spend a lot of time in wonder or horror, without a lot to do. They end up doing some important things, but ultimately it is up to godlike Oriens and Aurora to save the day.

This conflicts with the traditional maxim of YA literature, which is to let the kids bring about the resolution, with only a little guidance from adults or other powerful forces.

C.S. Lewis was a master of this practice. Most of the action in these books involved young people attempting to solve a problem or fulfill a mission, and Aslan showed up very seldom, only when things had come to a true dead end for the children.

Michael and Laura do a lot of spectating.

Does this mean that Kenogaia is more a book for adults than children, despite its main characters being on the cusp of adolescence?

I don’t know that that’s a relevant question.

Kenogaia is a book that is itself, which I admire. There isn’t a sense of having to be bound by genre expectations or intended readership. It’s what the author wanted it to be, and it’s great fun for all the reasons I list above, plus more.

As a writer of the type of fiction that gatekeepers of traditional publishing find unsellable, I am always happy to read a book that does not go in for what the gatekeepers want.

At the same time, I can think of a number of teenagers who would appreciate the deeply-planned and executed edifice that is this book.

But it might never get to be on the front table at your local Barnes & Noble.