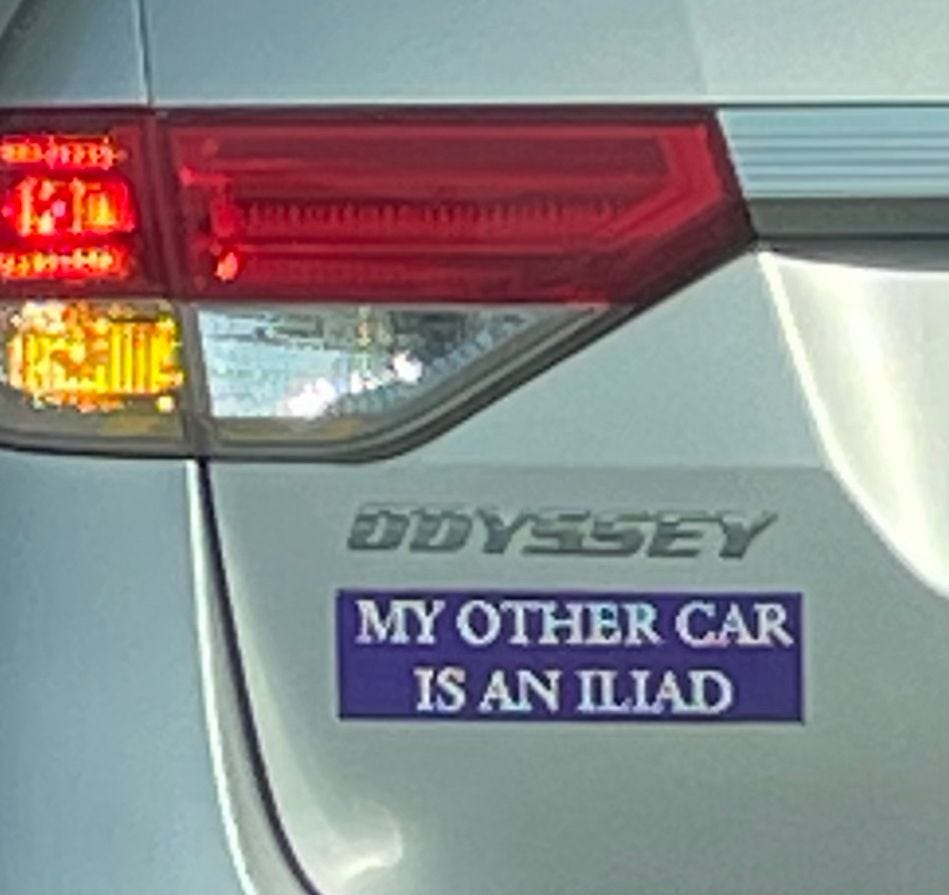

The Odyssey is a poem, and it is also a minivan, and it is also an English word meaning “a long journey full of adventure.”

The end of the Odyssey is now a major motion picture directed by Uberto Pasolini and starring Ralph Fiennes and Juliette Binoche.

Someday, a review of that movie.

Today, some thoughts on putting the Odyssey, the poem, into English.

I’ve already written about my admiration for Emily Wilson’s version, which, among its many virtues, allows 21st-century 9th graders to read the poem with enjoyment. It is certainly not Shakespeare simplified (an abomination, in my opinion), but its tidy beauty makes it quicker reading than many of the choices out there.

Which brings me to the latest translation, by Daniel Mendelsohn. I will always remember the day that we both presented papers as graduate students at a conference, and the professor who introduced us fell over himself with gushing praise for Daniel (who was his student), and when he came to me, mispronounced my last name.

Since then, Daniel has done a lot of excellent things, especially with the Odyssey and translations, so it makes sense that at a certain point he’d want to actually translate the Odyssey for publication.

It’s clear from his note on the translation that he has thought deeply about this work, especially about the rhythm and sound of it, and he decided on a version which is quite different from Emily Wilson’s.

In fact, it feels to me a lot like the translation of Richmond Lattimore (1951), the version which Daniel and I grew up with long ago. I loved that version, because it stayed close to the original Greek.

(So close, in fact, that the professor for whom I TAed in a large lecture Classical Mythology class suggested that in order to properly enjoy Homer, one should go to a bar with the book, order a pitcher of beer, and read and drink. Roundabout the end of the first pitcher, she claimed, the whole thing would all come clear!)

To me, this is the cardinal question with translations of the Iliad and the Odyssey: do you try to preserve the strangeness of the Greek text to non-Greek speakers by enriching the English text with complexity, or do you emphasize the accessibility of the story to the ancient Greeks by making the English text accessible?

For me, Professor Wilson does both. That’s why I like her version so much.

Mendelsohn opts for outright complexity.

That means that one line of his translation is noticeably longer than one of Wilson’s, and that each line packs a lot into it: the spellings of the names are more complex (I don’t know how to reproduce the umlaut and accent above the same letter on the name Atreides) and the allusions less transparent, the vocabulary is more archaic, the syntax more subordinated, and the sentences themselves are longer.

Here’s a sample from Book I:

With this in mind, then, Zeus addressed a word to the immortals.

Outrageous! Look how mortals heap blame upon the gods!

They like to say that we are the source of their ills, but if they have

More than their share of woe, it’s through their own heedlessness.

‘More than his share’: So it was just lately with Aigisthos,

who first married Atreides’s wife, then slew the man as he came home—

This, though he knew in advance of his looming ruin, for we’d warned him,

Having already sent down Hermes, that keen-sighted slayer of Argos,

To tell him, ‘Do not slay the man, nor woo his wife.’

Compare this to Wilson:

[Zeus] told the deathless gods, “This is absurd!

that mortals blame the gods! They say we cause

their suffering, but they themselves increase it

by folly. So Aegisthus overstepped:

he took the legal wife of Agamemnon,

then killed the husband when he came home,

although he knew that it would doom them all.

We gods had warned Aegisthus: we sent down

perceptive Hermes, who flashed into sight

and told him not to murder Agamemnon

or court his wife.

Is one translation “better” than the other? They are both beautiful and so obviously toiled over in love, that it becomes a matter of personal preference.

After Lattimore and the pitchers of beer, in my old age, I prefer accessibility.

I loved it when a student of mine, after reading Professor Wilson’s Odyssey, told me that the poem had been ruined for her. “Odysseus is horrible!” she complained. “He cheated on his wife for years with two different goddesses while she was faithfully waiting for him for 20 years!”

This is something that usually only comes to a student when they have actually read the book. If they have not, it’s all the Cyclops, the Sirens, and if you’re lucky, Princess Nausicaa.

I have been avoiding The Return, that new movie by Christopher Nolan, because I mostly do not like movies about Greek mythology. Everybody always has British accents and they look like they’ve been rolled in sand and desperately need a shower.

But I’ve watched the trailer now, and it looks not terrible, and possibly will watch the whole movie—soon.

Watch this space.

Thanks for this correction, mj. I had a dim awareness that maybe the Nolan version wasn't out yet, but I didn't investigate closely enough.

Hi, really like the article. I have read stephen fry's version of the odyssey and I loved it but I've heard that it's not the most accurate representation of odysseus. I am now in the middle of reading wilson's translation and I am dreading disliking odysseus by the end of it, considering how my favorite part of the whole thing is the love story between him and penelope lol. Also minor correction, The Return is directed by Uberto Pasolini. Nolan's adaptation of the book of is yet to be released.