This is a bonus newsletter based on some research I did for the most recent newsletter about Arachne. Some of this is likely to be in my chapter on the Roman reinvention of Greek Mythology in THE INVENTION OF GREEK MYTHOLOGY.

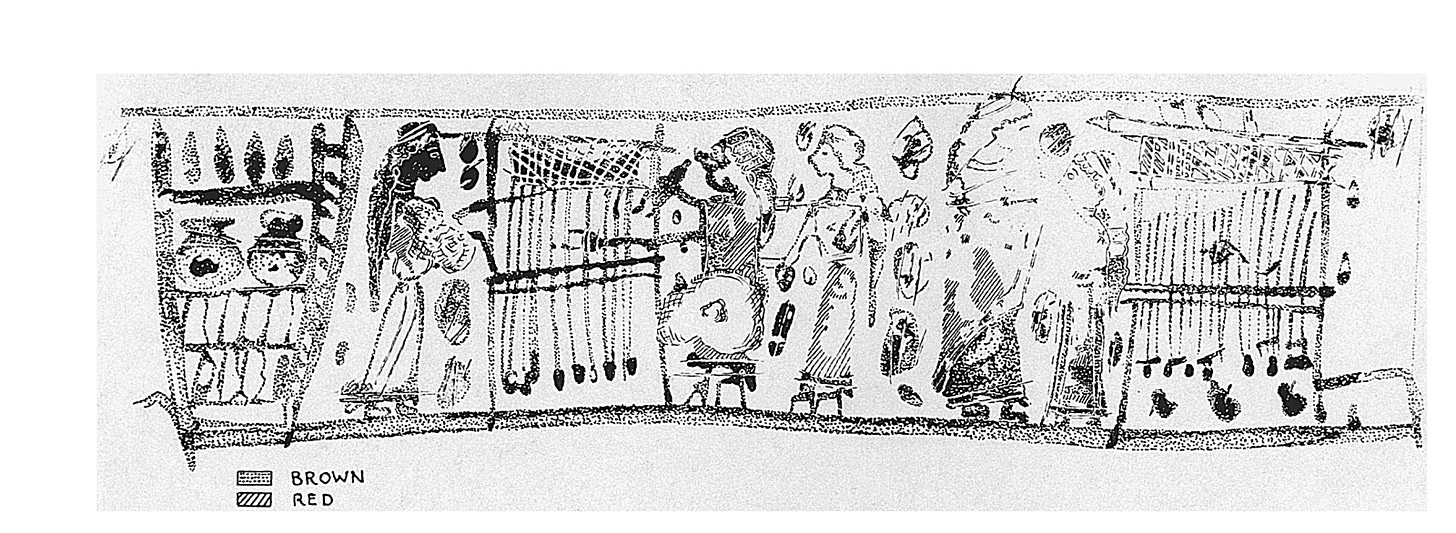

Take a look at the picture featured below. It’s a rendition of a scene on a painted vase (a small perfume jug) from Corinth dated to about 600 BCE, about the same time that the Greek myths were really cranking up to be considered and retold by actual writers of ancient Greek—and artists were beginning to depict them on pottery like this.

Before about 700 BCE, there were no written myths and nearly no pictorial representations of the myths—at least none that we can identify for sure.

So when something like this vase is discovered, everyone who loves Greek myths is eager to find some picture that looks like a tale we know.

That’s why this vase is purported by some scholars to be a picture of the weaving contest between Arachne and Athena that my previous newsletter discussed.

This is an incredibly detailed scene for such a small jug. The artist clearly took pains to depict a wealth of objects and clothing and a variety of kinds of people. The circular areas, unfortunately, are those places where the clay is pitted and the painting is interrupted.

Take a close look. What do you see?

I’m not an expert in ancient weaving, but I’ll describe it from my perspective.

I see two upright looms, first of all. That’s what women used to make cloth in the ancient world. You would hang threads vertically (the warp) on the loom and weight them with loom weights to keep them straight. You would then take more thread and loop it horizontally (the weft) in and out around the vertical threads, tightening it all the while with a rod.

The dark-skinned, long-haired woman on the far left is doing the tightening with the rod, while her partner (also dark-skinned) is using a couple of tools that look like they’re for keeping the vertical threads even. Another, lighter-skinned woman on the older woman’s right seems to be assisting.

On the right, you have a taller-than-normal figure who seems to be holding a distaff, which is a stick on which thread is spooled. A smaller figure is facing her. Some of their cloth is woven, but they don’t seem to be working actively on it.

On the way far left, you’ve got a shelf with jars, and some roughly rectangular materials below. Dyes? Food? Hard to tell.

So is it a weaving contest? Well, there are two looms, but if it’s a contest, the competitor on the right doesn’t seem to be sweating it at the moment.

And if it is a one-on-one contest, what are all the other women doing there helping?

The tall one on the right is supposed to be Athena, because she’s tall, and goddesses are, of course, tall. But the paint is worn away and you can’t see her front, where you’d think there’d be some sort of Athena-like attributes, such as her aegis, the goat skin with the emblem of the Medusa.

What about the color of the skin of the weavers on the left? Is that important?

That is intriguing, because it does seem as if the artist has differentiated skin color with his or her paint, and the woman on the far left seems to be a princess type with flowing hair, a headband, and an elaborate, ankle-length dress with a fringe on the hem.

Her partner seems to be much older. Her body is more square, less slim, her nose longer, and her hair is tucked under a headdress.

I would love to say this is Arachne. According to Ovid, the Roman poet who tells her story 600 years after this pot was made, Arachne is from Lydia, a region of Anatolia (modern Turkey). Is the artist trying to tell us that this is a foreign woman?

Maybe. But dark skin isn’t always a reliable indicator of foreign-ness in Greek art. Sometimes dark skin just means the person has been out in the sun more often than lighter-skinned people. And it has nothing to do with whether they are enslaved or not.

What about the tall woman on the right? She could be Athena, sure, but is she in a contest? She could be Athena just watching over the weaving of ordinary women, in her aspect as mistress of weaving.

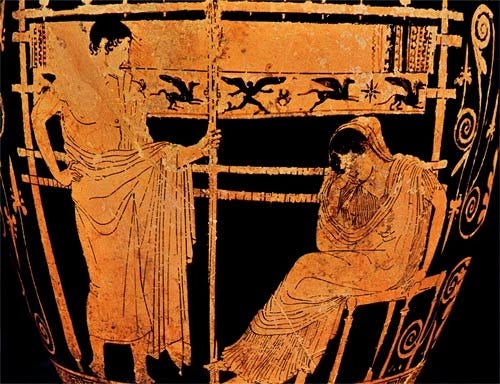

Or she could just be a tall woman. Take a look at this vase, which was done something like 50 years after our vase.

Do you get the point? Without any labels or writing in Greek, you’ve got to rely on the details of the painting to figure out whether this is a scene from a myth, or something from real life.

I’d wager it is a story, because the taller woman might just be a goddess and the princess type on the left and her older partner are so appealingly depicted.

If I had to guess, I’d say this scene—if it is a story—might be from a version of the Odyssey, and the princess type is Penelope, the long-suffering wife of Odysseus.

There is a lot of weaving going on in that story, and though Athena does not figure into a scene with weaving in it, she is a consistent ally of Penelope, Odysseus, and their son Telemachus.

In fact, there is a pretty well-known vase painting with a loom in it that includes Penelope and Telemachus, and here it is:

Penelope is sad because Odysseus is not around to kick out the 108 suitors who want to marry her and take over Odysseus’s rich estate. Telemachus is trying to be the man of the house, as we see here in Emily Wilson’s translation from Book 1:

…Go in and do your work.

Stick to the loom and distaff. Tell your slaves

to do their chores as well…

Coincidentally, one of Penelope’s assistants is Melantho, a name that means “black.” This might have nothing to do with the painter’s choice of shading in the women on the left. Then again, it just might.

The Odyssey was a well-known box-office smash in 600 BCE. Arachne’s tale? Not so much.

However, if the painter was thinking about the Odyssey, it isn’t from a scene that survived into the final cut of the poem, written down some one hundred years later.

So there are my two cents, for what they are worth. The message? Always look at the details. Look under the surface. Things may not be what they seem. And always, always know that creativity is endless. There is never one version of anything.