The Olympian god Hephaestus is often celebrated for his technological achievements.

He created female robot helpers, for example.

And he built a mechanical trap that snared his wife Aphrodite and her lover Ares while they were making love in the marriage bed.

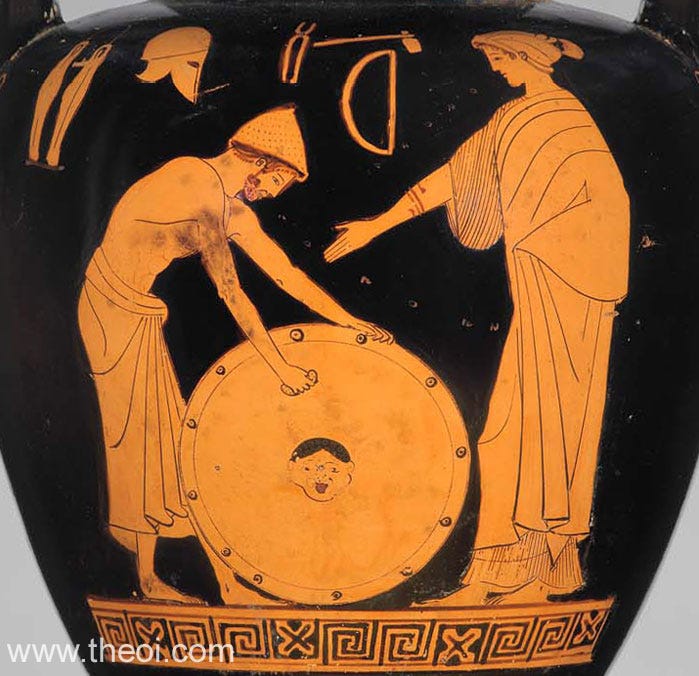

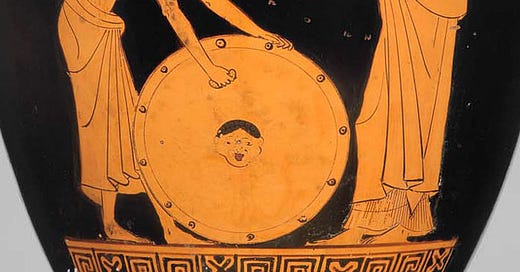

And in general, we think of Hephaestus as a blacksmith, someone who works with metal and makes useful things like shields.

But to me, Hephaestus is an artist—a creative.

He doesn’t make things just for their usefulness, but also for their beauty.

And his personality, shaped by his life experience, follows that of the artist.

I was reminded of this emphasis of Hephaestus when I read a review of a recent book by theologian, philosopher and Substacker David Bentley Hart, All Things Are Full of Gods, in which four characters from Greek mythology debate very deep philosophical subjects.

One of the characters in this book is Hephaestus, whom Hart presents as a materialist: that is, someone who believes that the only things that exist in the world are those the existence of which we can prove scientifically.

In other words, according to Hart’s Hephaestus, nothing is full of gods, and if the Greek divinities ever existed, they were probably… hmmm… super-strong aliens.

(Which puts me in mind of an original Star Trek episode, but that’s a post for another day.)

To understand the whole irony of that characterization, I would have to read the book. But on the surface at least, Hart is getting Hephaestus all wrong.

It’s true that if you’re going to write a book with characters from Greek mythology, and one of them has to be a materialist, then maybe Hephaestus (because of his orientation with technology) is the best choice.

I don’t know. I think Apollo would be fine, too. He’s a pretty bloodless intellectual.

Or Athena. Another immortal who’s matter-of-fact about most things.

Heck, even Zeus might be a candidate for the materialist interlocutor. He could say that his lightning bolt is “just electricity.”

Hephaestus doesn’t resemble any of these divinities. In fact, he could be considered the most sentimental of the Olympians.

He is the only (or nearly the only) divinity among the Olympians who is disabled and whose physical appearance is repulsive. One version of his myth states that Hera, his mother, took one look at him and threw him out of Olympus.

Another version states that Hephaestus had attempted to take the part of his mother in a dispute with Zeus, and Zeus threw him out. Hephaestus fell and fell, and when he landed, “There was little life in me.”

This means that Hephaestus has no physical strength or personal charisma, and has to rely on his techne (that is, his skill) to merit the status of an Olympian.

Hephaestus does not enjoy a privileged position in the hierarchy of his family. He does not produce demigods with human mothers. He sits at his forge (his studio) making things.

He is gentle, humble, non-threatening, and generous.

Very different from the typical Olympian.

This type of profile tallies with that of many artists, many of whom do have inner hurts and who channel those injuries into beautiful creations. Often, like Hephaestus, they fulfill commissions for free, just for the joy of it—and sometimes because people take advantage of them.

For an illustration of what I mean, let’s consider something Hephaestus makes: the Shield of Achilles.

This item is described in Book 18 of the Iliad. It is commissioned by the goddess Thetis, Achilles’ mother, as a replacement for Achilles’ original shield, which his friend Patroclus lost when he was killed by the Trojan hero Hector.

Does Hephaestus negotiate a price for this commission? No, he’s glad to do it, because of his previous friendship with Thetis and because she is upset about her demigod son:

Her answer’d then the artist of the skies.

”Courage! Perplex not with these cares thy soul.

I would that when his fatal hour shall come,

I could as sure secrete him from the stroke

Of destiny, as he shall soon have arms

Illustrious, such as each particular man

Of thousands, seeing them, shall wish his own.”

And what does he create?

He fashioned first a shield massy and broad

Of labor exquisite, for which he formed

A triple border beauteous, dazzling bright,

And looped it with a silver brace behind.

The shield itself with five strong folds he forged,

And with devices multiform the disk

Capacious charged, toiling with skill divine.There he described the earth, the heaven, the sea,

The sun that rests not, and the moon full-orbed.

There also, all the stars which round about

As with a radiant frontlet bind the skies,

The Pleiads and the Hyads, and the might

Of huge Orion, with him Ursa called,

Known also by his popular name, the Wain,

That spins around the pole looking toward

Orion, only star of these denied

To slake his beams in ocean’s briny baths.

(Translation William Cowper)

This is not just a technological marvel, massy and broad, with five strong folds, to ward off the blows of the enemy.

It is also, unmistakably, a work of art.

The text goes on for another 150 or so lines talking about all the metal (gold, silver, and bronze) and colored (purple grapes, “sable” earth) decoration that Hephaestus puts on the shield: two cities with their various inhabitants and activities, disagreements, and battles; a harvest of grain and a harvest festival; a vineyard with young people dancing; lions attacking a bull with townspeople and dogs helpless to stop the carnage; and finally, festival dancers such as you’d find in Bronze Age Crete.

This is an incredibly intricate piece of poetry, diamond-like in its kaleidoscopic facets. And the author knew what he was doing when he composed it—by describing the shield, he becomes like Hephaestus, identifying the human act of creativity with divine power.

Hephaestus, in turn, becomes not only an artist, but a story-teller, an observer of life in Greece, a celebrator of the joys and sorrows of humans’ interaction with each other and nature.

That’s not a scientist who thinks that all that exists is what you can perceive—or prove in an equation.

I think all creative people should read the Iliad with Hephaestus in mind, looking for the places where he appears. The details of the stories about him might clash a bit, but the thread is beautifully woven into the narrative: Hephaestus has many skills with technology, but his heart is in the beauty of his art.

Thanks for reading! The Iliad is such a fascinating document, especially for being 2,700+ years old. I never get tired of reading it.

I also haven't read All Things Are Full of Gods, so I can't really say much, but there's something strange about making any of the gods materialists. That's such a modern philosophy. I would imagine that, for ancient people, working with the transformative power of fire (as in a forge, pottery kiln, or glass work) must have seemed almost magical. The creation of automatons (and also of Pandora, although there were other gods involved in that story) shows how impressive his techne was. His artistry is at such a level that he's almost able to create life.