I firmly believe that everyone has a story.

It may be a story for a million people to read, or it may be one just for oneself.

But it’s in there, and it’s there to be told.

So, in other words, everyone has a little Hephaestus in them.

Apropos of all that, I had a revealing conversation with someone this weekend as I was sitting at a table at an event selling my novels.

“Being a writer is a big step,” she said. “To make that decision, you have to know you really want to do it.”

I nodded, but added, “Being an author, a writer who wants to publish and make their stuff available for strangers to read, that’s a big step. Just being a writer, I think everybody should do.”

It’s become easier and easier to be a writer. In ancient times, ink and papyrus were expensive. Books had to be published by hand. Only rich people with leisure could be writers.

A thousand or so years later, the printing press made publishing easier. But type still had to be set by hand.

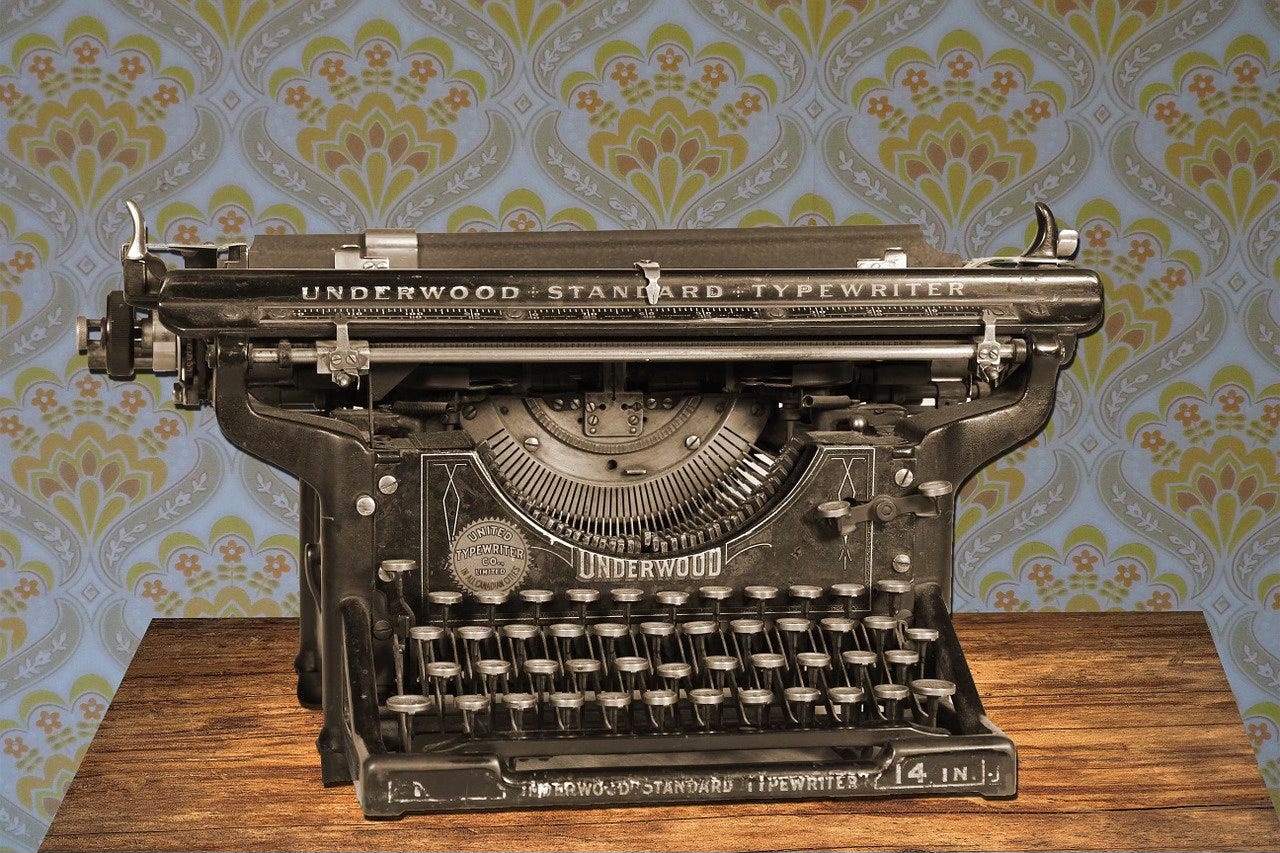

Then came the invention of the typewriter. I loved when I got my first one. I loved that the letters looked so much like letters in a real book. Writing on a typewriter inspired me.

Then came computers and word processing, making the correction of errors so much faster.

Finally, print-on-demand and e-books made it so that no one ever had to send their manuscript to an agent or publisher ever again.

Everyone could be their own publisher.

Now, with AI, I suppose we are set to make the production of writing from brain to page simpler, too.

It’s as if not only the divine forge of Hephaestus has become available to everyone. It seems it won’t be long before Hephaestus’s very creativity will be available to all of us with the touch of a button.

We will be gods.

Unless we won’t.

I don’t know what AI will do to the landscape of fiction. Will it be able to just string together tropes and traits and create novels that people want to read?

Will “authors” effortlessly push a button and create bestsellers?

Or is fiction something that truly has to come from the human brain alone?

Greek mythology has something to say about this. You knew it would.

Way back as long ago as the writing of the Iliad, authors could envision bots.

Hephaestus, in fact, invented a set of female robots who helped him in his artists’s studio. This is from Book 18:

but there moved swiftly to support their lord handmaidens wrought of gold in the semblance of living maids. In them is understanding in their hearts, and in them speech and strength, and they know cunning handiwork by gift of the immortal gods.

(Translation A.T. Murray)

I guess you could call two of these automatons Siri or Alexa; Alexa makes sense because it is a shortening of the Greek name Alexander, which means “defender of men.”

Like AI with its ability to scrape the internet for knowledge and write original content, the golden handmaids had “understanding in their hearts” and “cunning handiwork by gift of the immortal gods.”

Another set of golden automatons, the Keledones, Hephaestus made for Apollo to install in his temple. These creations could sing—but it doesn’t say whether they made up their own songs.

To find females who really did have the ability to create and inspire, you have to go back to the originals.

Those goddesses were the Muses. These were divinities, not robots, who have been famous since antiquity for inspiring creative people (especially poets).

You might wonder why help with creative activities might be the province of a group of female beings, and interestingly, there is a tantalizing piece of evidence from Bronze Age Ugarit (north Syria) that might give a clue as to what’s going on.

The Kotharat were a group of (possibly seven) goddesses who were in charge of pregnancy and childbirth. Their name resembles that of the god Kothar-wa-Hasis, who is the Hephaestus of Ugaritic mythology.

The root of both their names means “skilled” or “clever,” and though there exists no specific link between Kothar and the Kotharat, it makes sense that a group of goddesses interested in birth might have something to do with the metaphorical birth of ideas and creations.

(Much later, Plato creates a character in one of his dialogues, a woman named Diotima, who says that the teacher is the midwife that helps students give birth to new ideas.)

Are Hephaestus’s golden handmaids and the Muses themselves linked to the Bronze Age skilled goddesses of pregnancy and childbirth? We can’t tell right now. But there’s an intuitive link there nonetheless.

So what does all of this mean to us, humble humans in the face of what seems to be the divine AI?

Let’s not get intimidated.

Even the Greeks felt that humans were in a way superior to the gods because, being mortal, life mattered to them more.

The authentic voice of a human telling a human story is incredibly powerful.

It doesn’t matter that much to me whether AI will or will not be able to write fiction that touches the human heart.

To me, what matters is that we humans write our own unique stories from our own treasury of knowledge and memory.

That will always be precious, always be needed.

A good friend of mine has written about the future of AI in an especially good book where a space traveler to Pluto has an AI personality literally in her brain and always available to talk to. It’s fascinating to find out what the possibilities might be.

That’s what a human is capable of—envisioning possibilities.

Have you read David Bentley Hart's All Things Are Full of Gods? Not only is Hephaestus a character in the dialogue, but it also addresses the question of AI and minds. (I must admit that it sits on my shelf, still unopened!)